We are nearing 800 days since the first COVID-19 lockdowns began in Ontario. Those on the front lines – nurses, pharmacists, personal support workers (PSWs) and others – have borne the brunt of the uncertainty, stress and trauma unleashed by the virus.

In the earlier days of uncertainty and anxiety, these folks dutifully arrived at their posts while all around them the world seemed to simultaneously fall apart and stand still. Without the dedication of those pharmacists who administered millions of COVID vaccines, those nurses who faced day-to-day risks just doing their jobs and those PSWs who took care of our elderly loved ones – how would we ever have gotten through these past two years?

It may be tempting to believe that the occupational stress we are now seeing across health professions is simply a function of the extraordinary circumstances we have lived through – and that now with some hope of a retreat from pandemic conditions, everything will get back to normal.

But for those front-line health professionals unrelentingly challenged by the pandemic, the “normal” everyone is so keen to return to may in fact be the last straw. Occupational surveys suggest we may soon experience a tsunami of retirements, resignations or shifts to part-time work among health-care professionals – for them, “back to normal” means a return to exhaustion, disrespect, overwork and burnout.

Politicians of all stripes, recognizing the implications of a health-care workforce in free-fall, are attempting to address the issue by throwing money at the problem. One-time only bonuses or salary top-ups to reward workers and encourage retention may appear to be a positive step forward. For the responsibilities they assume, the education they require and the stress they endure, who could begrudge these workers a boost in pay? For some, it isn’t even about the actual money but rather the respect and thanks the money acknowledges.

Money is important, but what is more important will be the “normal” post-pandemic workplace that lies ahead.

But politicians who believe a few extra dollars is all it will take to keep the health workforce afloat are likely in for a rude awakening. Money (and the respect that it connotes) is important, but what is more important will be the “normal” post-pandemic workplace that lies ahead. Staffing ratios, access to proper equipment and supplies, sufficient breaks, workload, technological overload, disrespectful patients and overbearing managers are all more important drivers of occupational stress and burnout than salary alone.

Failing to address these underlying pre-pandemic workplace issues – or believing that a nominal bonus adequately compensates individuals – is not only unfair, but also will likely be ineffective in preventing the hemorrhaging of workers we are seeing. Of course we must pay health-care workers what they deserve (difficult though this may be with Ontario’s cap on public sector pay increases). If we are serious about addressing labour shortages in health care, it will require a re-examination of the daily conditions of work that were difficult before the pandemic and that got considerably worse over the past two years.

There is much to do. Decreasing staff to patient ratios to allow for proper and human care, providing adequate technical support to assist professionals and allow them to focus their efforts more appropriately, ensuring access to sufficient supplies and equipment so people can simply do their jobs, are just a few. Perhaps even more fundamentally, acknowledging systemic bias and discrimination, addressing harassment by patients and workplace bullying and improving communication between professionals are all essential.

Health-care work is difficult; most health care workers knew this when they signed up. They accepted the challenges because of the rewards of caring for others. What they never signed up for were workplace conditions that undermine their professional integrity, disrespect them as people and leave them physically and emotionally exhausted at the end of each shift. These workers are starting to vote with their feet and leave their professions.

Expedient solutions, like a $5,000 bonus, will be ineffective. Instead, we need to listen to our front-line workforce and reshape health-care settings so that health-care workers can provide better and more humane care for their patients.

More News

Image

Pharmacy alum sees change in acceptance of Indigenous cultures in health care

During Deborah Emery’s 40-year pharmacy career, she provided care in Sioux Lookout, Thunder Bay and Manitoulin Island.

Read More

Image

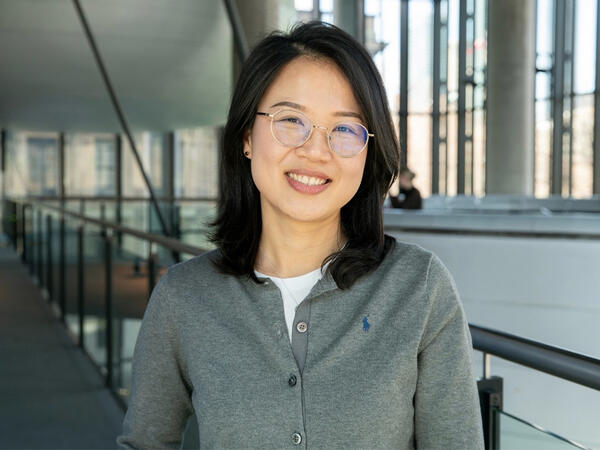

Grad to Watch: Jackie Fule Liu’s research focuses on better outcomes for diabetes patients

A recent PhD graduate, Jackie Fule Liu combines hands-on skill and big-picture thinking to help tackle diabetes care challenges.

Read More

Image

U of T community members recognized with Order of Canada

Congratulations to Dean Emeritus and Professor K. Wayne Hindmarsh on his appointment.

Read More